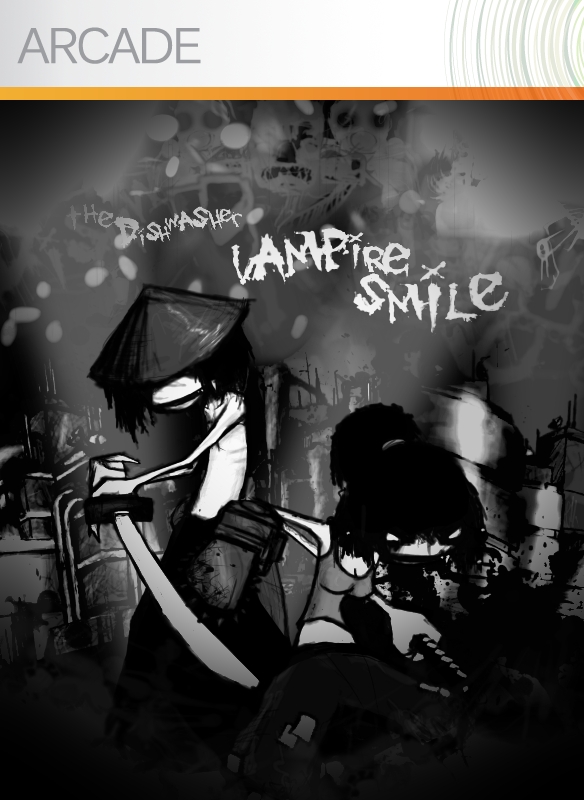

I scan for the next body, catching it with my chainsaw. This is how Ryu Hayabusa moves in his dreams. Long, vibrant patterns, defined as much by their artistic expression as they are by their symmetry, unfurl. Not punch, punch, punch, kick, throw but beautiful abstract patterns like those found on Moroccan tile and Afghan rugs. But the game compresses and folds my flails into lethal form. I rap on the controller and flick the dash-move compulsively. I feel like I’m spamming: lashing out wildly in an inexact combination of button presses. I’m given control over a vast, intricate meat grinder, and all the program can do is throw more meat at it and hope a bone gets caught in the bearings. The only time I’m asked to play Simon with the bad guys-the matching game of well-timed blocks and attacks that most fighters rely on-is when I tap X to cut their heads off. I can move anywhere on the screen I want. To be fair, Vampire Smile is also a straight line, but it lets me dance along the way. We walk in a straight line with chains on our feet, even when we choose the direction. A cold and mechanical algorithm looms over us, and all we can do is push left, right, B, or A. We call it play, but our options in a videogame are generally so narrow that it feels more like being dominated. They pose the question: Why do we like games in the first place? As do the ironic Guitar Hero-style mini-games that contrast the fluidity of combat. Vampire Smile’s plot is initially ludicrous-my protagonist is a psychopath who believes she is ravaging an evil corporate empire while actually murdering her caretakers at the ward-but winds up commenting on the nature of play. By that time, I had already ripped a gapping hole through it, exposing a frantic interplay in the synapse between player and machine. Most games hide behind their illusion, but before it ends, Vampire Smile starts to pull back the curtain. My mind is acute, racing as it exchanges impulses with an arabesque of binary digits, which lies beneath the maya of a hundred goons being slaughtered in grotesque fashion. This may look like a mindless act of violence. Then I rain down on the corpse with my chainsaw-arm.

#The dishwasher vampire smile review android#

I redirect in midair, slice through android rubber, and finish it off with my machine gun. I choose an easy target and dice him up real fast. On cue, I’m jumped by a group of mercenaries. The attacks are so over-the-top, so easy to pull off, and so versatile that combat becomes entrancing. I plunge into similar-looking bloodbaths, killing the same animations of hitmen a thousand times over. I’ve been given a sword, a chainsaw, a giant pair of scissors, an oversized hypodermic needle, a pair of meat cleavers, a machine gun, and a very long list of moves, which I link into an assault that fuses the routine of a hack-and-slash with the ecstatic possession of a voodoo dance. Their sole purpose is to serve as a fresh stock of bodies to wail on. They need more.Īs I play, I’m frequently ambushed by goons-cut-rate thugs who look like caricatures of the type who’d hang out at the Chatsubo in Chiba City.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/14274011/screenlg4.0.jpg)

In doing so, he makes an undeniable statement. It’s as if Silva’s intent was to take videogames’ worst habits and exploit them. Yet unlike these games, Vampire Smile doesn’t require much skill. And combat ranks among the twitchiest, seated alongside Devil May Cry and God Hand. The story is edgy to the point of incoherence. Naturally, a dark, post-apocalyptic setting is employed. James Silva, the mastermind behind the carnage, has taken the tricks developers use to appeal to a hardcore audience, and pushed them to the brink. Even the act of moving streaks the screen in blood. The mood is constructed of cheap thrills: button mashing, gratuitous violence, and money shots at the push of a button. In many ways, Vampire Smile is the videogame equivalent of grindhouse.

But I relished in these facets and pressed on, twirling through sumi-e stained shards of industrial ruin. I would have complained that combat is a repetitive exercise in slaying ninjas. I’d have rolled my eyes at The Dishwasher: Vampire Smile’s emo gore-worship. If I hadn’t just massacred a small army in one long fluid swoop of animalistic brutality, I’d have snickered at those lines.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)